Summary

Canada is more trade-dependent than the U.S.; however, if the U.S. imposes a 10 or 25% across-the-board tariff, it will likely result in retaliation, harming both countries. Some industries, like automobiles, would be particularly hard hit.

Determining what Trump wants (e.g., border control, reduced illicit drug flows, more defense spending) and negotiating in good faith could reduce the threat of a trade war to nothing more than a negotiating position.

Trump has used tariffs in the past, so this needs to be taken seriously. Understanding which products are most vulnerable and presenting those at the “Team Canada” table will be crucial for Manitoba and other Canadian provinces.*

* “Team Canada,” is shorthand for different governments and parties working together. The phrase has been used many times, including on overseas trade promotion missions, trade negotiations and the like.

Analysis

Donald Trump won the U.S. election on Nov. 5, 2024. During his campaign, Trump indicated two items of note: a significant reliance on tariffs and deporting people without proper authorization from the U.S.

First, he noted his intention to apply a 60 per cent across-the-board tariffs on all goods coming from China, and a 10 per cent tariff on goods coming from the rest of world (CNN Nov 8, 2024).

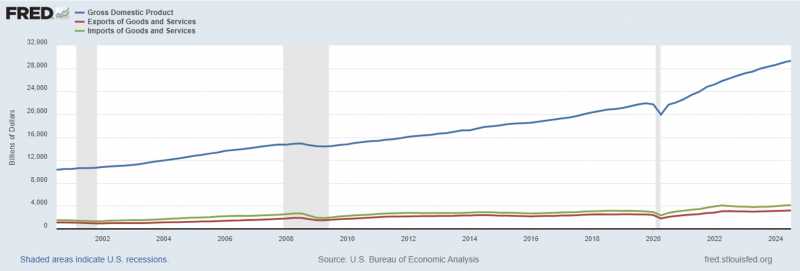

To understand of how trade-exposed the U.S. is, we consider U.S. exports, imports and GDP. Using the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’s FRED database, we can see all three have risen over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1: US Quarterly GDP, Exports and Imports (Quarterly at annualized rates)

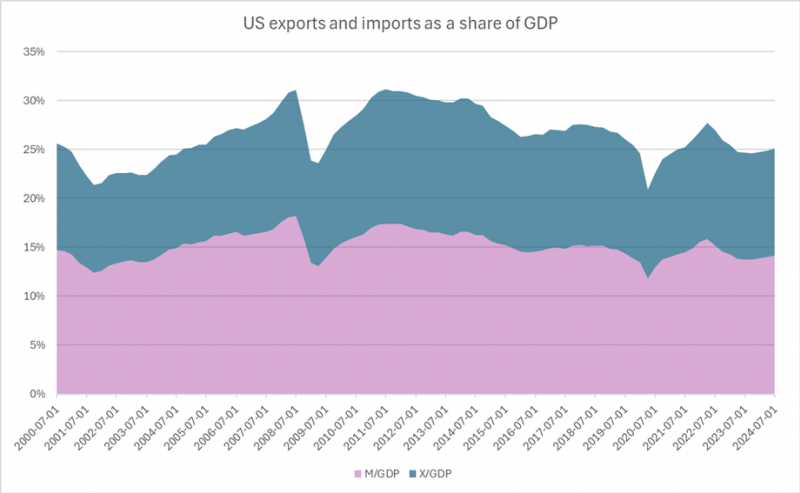

However, when examining the share that imports and exports form of the U.S. GDP, we see that their trade share

((exports + imports)/GDP) has declined from a high of 31 per cent in 2012.

Imports make up about 14 per cent of the U.S. GDP and exports about 11 per

cent, combining to a total of 25 per cent as of July 2024 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: US Export and Import Share of Quarterly GDP since 2000

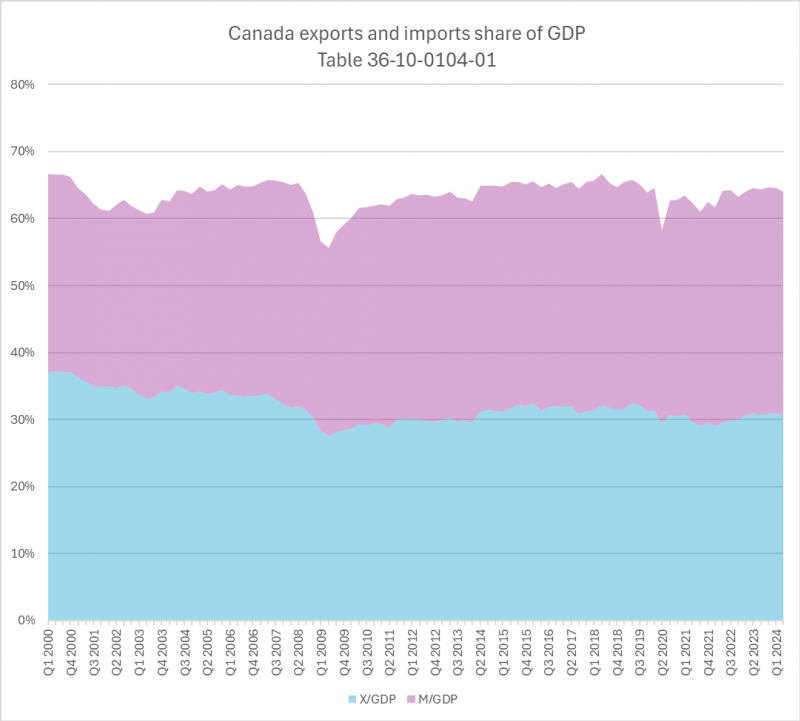

Canada’s economy is much more trade-dependent, but our trade dependence has also decreased, falling from a high of 67 per cent

(imports and exports) in 2000, to 64 per cent in Q2 of 2024. During this

period, exports were 31 per cent and imports were 33 per cent.

As Alexander Panetta wrote (CBC, Nov 26, 2024), Trump recently escalated matters for Canada and Mexico, stating

his intent to impose a 25 per cent tariff on all goods from the two nations.

The reasons cited include curbing the flow of drugs and people into the U.S.

Trade complexity

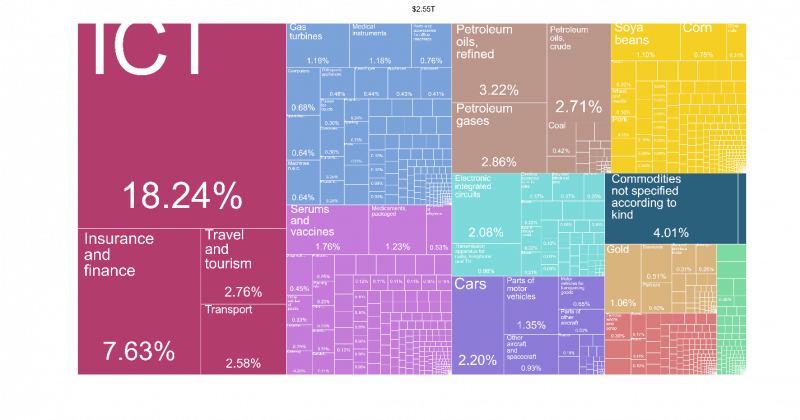

The U.S. exports approximately $2.55 trillion (larger than Canada’s economy), with 16 per cent destined for Canada, 15 per cent to Mexico and 9 per cent to China, according to The Atlas of Economic Complexity.

Figure 3: US 2021 Export Flows (Atlas of Economic Complexity)

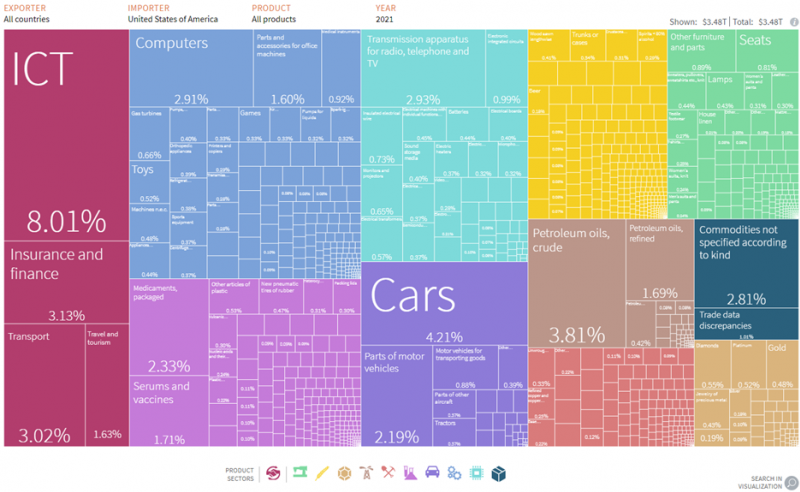

The U.S. imported $3.48 Trillion in goods and services in 2021 (Atlas of Economic Complexity).

Figure 4: US 2021 Imports $3.4 Trillion (Atlas of Economic Complexity)

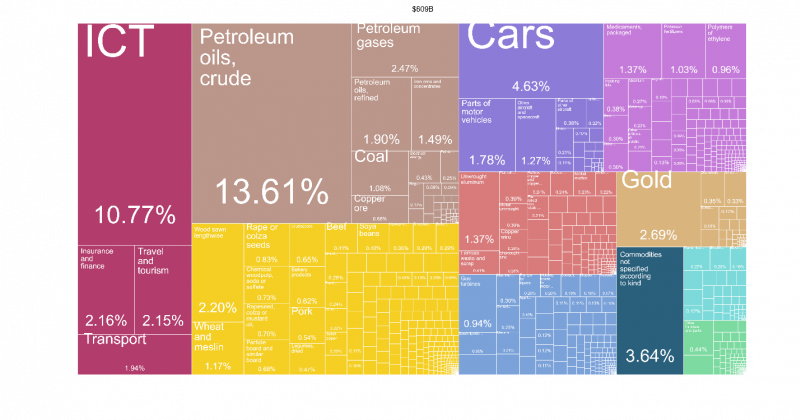

Canada’s 2021 exports totaled $609 billion and 73.39 per cent were destined for the U.S., and 5.13 per cent destined for China.

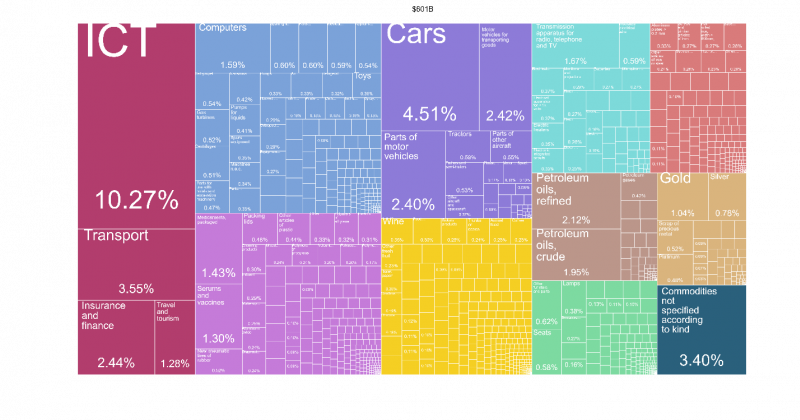

Canada’s 2021 Imports were $601 billion, with $56.85 per cent from the U.S. and 11.90 per cent from China.

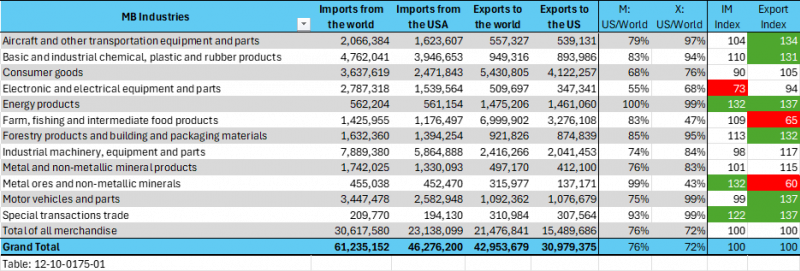

To bring it to a Manitoba export/import context, we can look at 2023 trade figures.

To bring it to a Manitoba export/import context, we can look at 2023 trade figures.

Focusing on Manitoba’s 2023 trade, most of the province’s trade is with the U.S. (72 per cent of all exports and 76 per

cent of all imports) across all products. When we index individual product

categories against the overall share, those marked green are at least 20 per

cent above average, and those marked red are at least 20 per cent below

average. Key exports include pharmaceuticals, hogs and pork, canola,

electricity and buses.

We recommend diving deeper into the specific products using Harmonized System (HS) codes—a standardized numerical system used to identify and categorize products traded internationally—to identify the largest-value and most vulnerable products. Tools like the Canadian International Merchandise Trade Web Application can help.

Suffice it to say, Canada and Manitoba have significant vulnerability to trade disruptions if new tariffs are introduced.

Even without retaliation, applying tariffs would significantly impact U.S. citizens.

Considering the issue

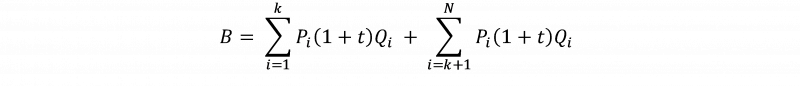

For example, if we consider the budget constraint of people (B), adding a tariff to all goods effectively multiplies prices by (1 + tariff-rate). At a 10 per cent tariff rate, prices would rise accordingly meaning, for products with few domestic substitutes, people would have no choice but to pay more, potentially cutting spending on other goods and services. The budget formula below breaks the budget into essential (1 to k), and non-essential (k+1 to N) goods and services.*

* For an arbitrary value of k, technically speaking.

For companies with significant trade in commodities or intermediary goods, this would be particularly disruptive. A

good example of this is the automobile industry, airplane and bus making industries.

For exporters like Canada, certain products could lose out to import substitution by U.S. producers, leading to reduced exports and slower economic activity. While some of our goods could potentially be sold domestically or exported to other markets, finding substitute buyers would take time—and for some products, substitutes may not be found at all.

Applying a 25 per cent tariff would be even more disruptive to both Canada’s and the U.S.’s economies. Complex supply chains would be severely disrupted, potentially weakening entire industries in the short run (auto industry). Even if Canada / Mexico did not retaliate (and they need to imply that they will if necessary). This appears to be primarily a negotiating tactic for broader policy goals. However, the incoming administration has previously imposed tariffs targeting specific industries or products, so the threat must be taken seriously.

A clear understanding of what the U.S. administration seeks in terms of trade negotiations, border control (illegal people and goods flow) and other priorities is essential. Collaborating as “Team Canada” and aligning national and provincial priorities will help address these challenges effectively.

Some industries in the U.S. may struggle to find the labour needed for import substitution, even with sufficient plant and equipment. This challenge would be exacerbated if the new administration succeeds in deporting large numbers of people, disrupting industries that heavily rely on undocumented workers. In the past, this has included sectors such as horticulture and meatpacking, among others.

In conclusion, navigating the labour shortages caused by deportations and the complexities of U.S. tariff policies will require careful coordination and strategic planning. Industries in both Canada and the U.S. face significant risks, making collaboration and clear negotiation strategies essential to mitigating potential economic disruptions.